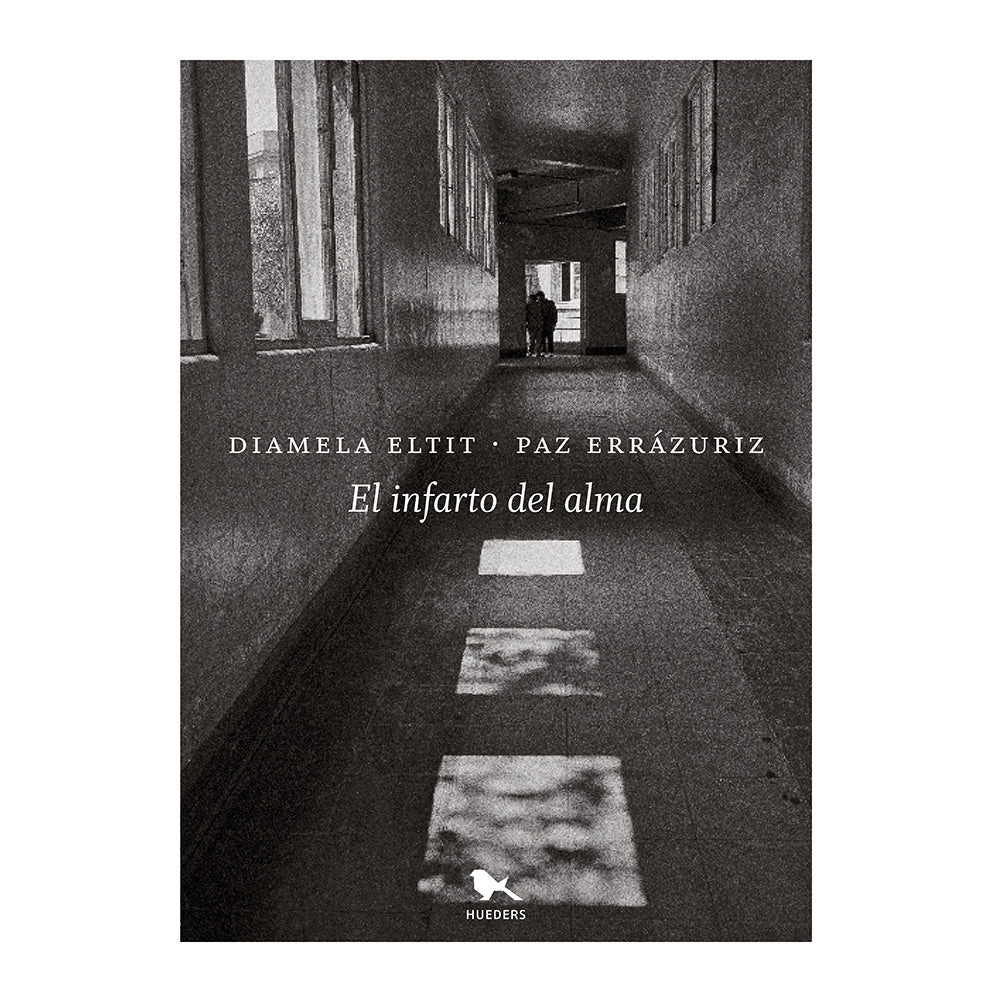

Today, Chile is on my mind. Having spent the better part of the last three months crafting my Master’s thesis on the photographs of Paz Errázuriz, I would now like to return to my first encounter with her work. Soul’s Infarct, 1994 is a photobook made in collaboration with the writer Diamela Eltit in the aftermath of the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. It occupies a gray area between visual art and literature. In the context of post-dictatorial and neoliberal Chile, this project centers on socially discarded and forgotten human subjects enclosed in the country’s most famous mental institution. To say that Errázuriz’s and Eltit’s is upsetting to a regime that valued economic productivity above human life would be an understatement. Interweaving text and image, Soul’s Infarct is composed of striking black-and-white photographs of anonymous, chronically ill, and mostly indigenous patients holding hands, laughing and embracing, and a range of texts which oscillate between descriptions and narrations, letters, and diaries.

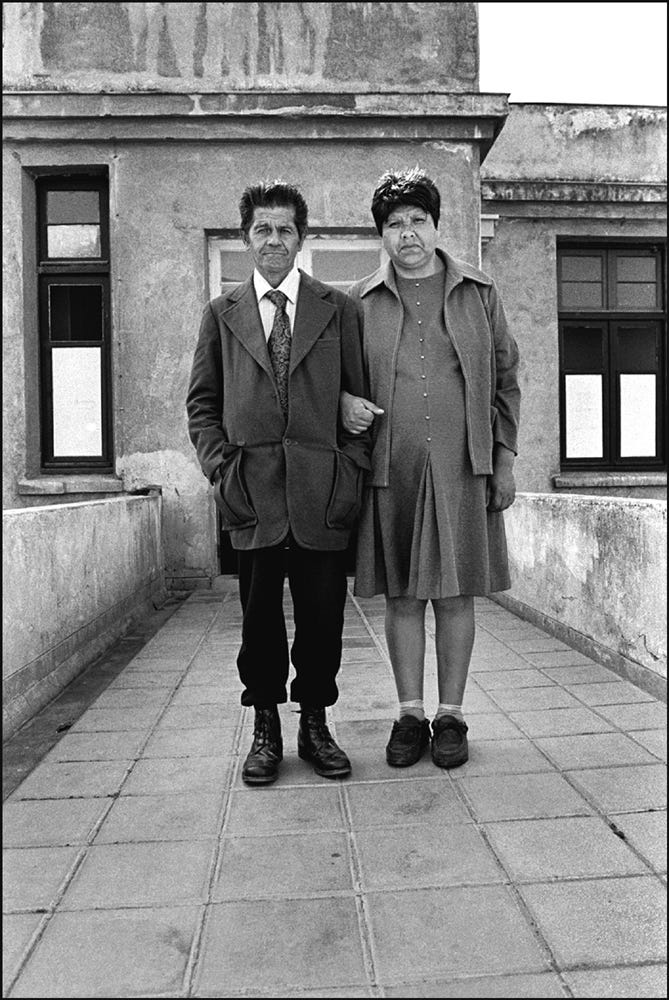

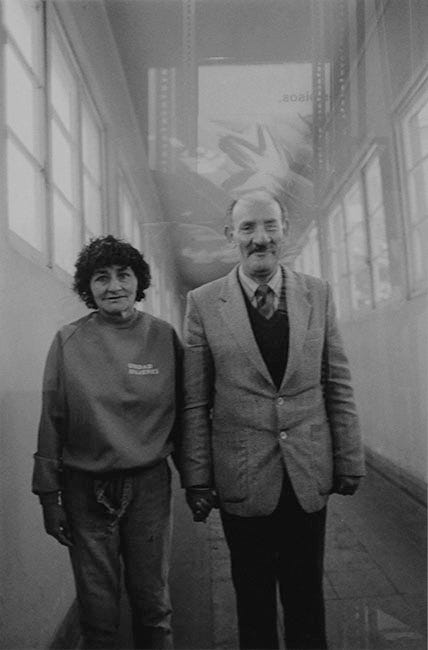

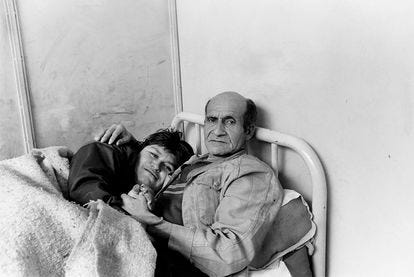

The unifying thread running through Soul’s Infarct is a peculiar dialectic of love, in the specific Spanish meaning of the word querer, signifying both ‘’to love’’ and ‘’to want’’. While the book deals with social abandonment, displacement, loss of identity, and a physical absence from the world, love serves as an overarching metaphor. This is hardly surprising as the cultural associations of madness/love and illness/love are historical fact. Soul’s Infarct aestheticizes a life of marginality through a semi-imagined, semi-observed narrative of love. The subtle, seemingly effortless gestures of affection, visible in Errázuriz’s photographs create a sensitive point of tension in the images.

Given the history of this particular mental institution, which used to function as a sanatorium for people with tuberculosis, and the romantic associations of this illness, the choice of constructing the book around love is particularly brave. In a Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, Roland Barthes writes: “Every lover is mad, we are told. But can we imagine a madman in love? Never.” In Soul’s Infarct we do not need to imagine—the numerous voices of the disjointed narrative open up the photographs. They subvert and explore the clichéd idea of falling ‘’madly in love’’ through the asylum inhabitants ‘’who love each other with the same intensity as that of their illness.’’ Text and image create a lovers’ discourse that quite literally blurs the borders between madness and love. ‘’After all people fall in love like crazy. Like crazy.’’

Paz Errázuriz’s photographic work since the time of the dictatorship has been predominantly linked to the periphery. She photographed marginalized members of society in an attempt to counter the political authority that had condemned them to social ostracism. Visibility, we could say, is key to upsetting political repression. Hence, the body is of primary importance in these photographs. The men and women that Paz captures are the alienated, wounded, lonely bodies of people who do not exist for the world outside the asylum, but who nonetheless exist for each other. The fact that the patients are almost always captured posing and rarely caught off-guard is significant. This detail is a small, yet significant gesture of regained control over at body, be it only momentarily. The physical ticks and signals often associated with psychiatric disorders and the disregard for appearances as a by-product of social alienation are temporarily overcome in the act of posing for the photograph. Errázuriz exposes the type of body marked by a mental and/or physical disorder, which stands in stark contrast to the values cherished by a modernity praising vigor and beauty.

During the government of General August Pinochet, people used to search for their disappeared loved ones by showing photographs taken from the state registry (instead of more personal images), in an act intended to question both the institutional authority over people’s photographs and over their bodies. If these images were used in the hope to find someone missing, confirming a disappearance, then Errázuriz’s pictures in Soul’s infarct fill social absence and force its acknowledgment. This theme is present throughout Eltit’s texts. In Errázuriz’s photographs, these themes are magnified in the last pages of the book. The images of couples are followed by a display of the abandonment prevailing in the mental hospital. Empty corridors, dark staircases, and walls with crumbling and cracked paint present an image of a physical world falling to pieces, inhabited by people whose identities are just as fragmented and abandoned. Here is a heterotopia, in the Foucaultian sense—it is a space of deviation. Heterotopias are spaces populated by individuals whose behavior deviates from societal norms; for example, brothels, prisons, and mental asylums. There is a real indication of economic neglect. The photographs and texts constitute a form of re-insertion of those members of society who have remained voiceless, allowing them to enter the cultural sphere. Photography here acts as a testimony, bridging the gap between being and nothingness, urging the recognition of those marginalized individuals who would not otherwise have the voice to assert their neglected existence. Thus, Errázuriz and Eltit present us with a document, as much as an artwork, that uses a narrative of mad love to make fill a gap in the past and rescue memory. Created post-dictatorially, Soul’s Infarct suggests that the missing persons’ era in Chilean history did not end with the fall of the military government; rather it hid behind a different, crumbling façade.

NOTES

Loss, Jacqueline. “Portraitures of Institutionalization.” CR: The New Centennial Review 4, no. 2 (2004): 77–101.

Forcinito, Ana. “VOZ, ESCRITURA E IMAGEN: ARTE Y TESTIMONIO EN ‘EL INFARTO DEL ALMA.’” Hispanófila, no. 148 (2006): 59–71

Lorenzano, Sandra. “Cicatrices de La Fuga.” Debate Feminista 13 (1996): 221–52

Wow, powerful post. Thanks for sharing your commentary. There is a lot to think about here. “Roland Barthes writes: “Every lover is mad, we are told. But can we imagine a madman in love? Never.” You have encouraged me to study photography, this is fascinating.