Recently, a friend of mine said to me that ‘To grow up is also to give up’, as a joke. While I generally disagree, it got me thinking about one particular facet of growing up as a woman that has been tormenting me on and off since I was a teenager—aging physically. There is the not-so-obviously persistent fact that regardless of how much societal values have changed, a man’s desirability increases with age, while a woman’s usually decreases. And sure, today we are much better at revisiting gender bias when it comes to aging and really shedding light on the wonderful changes that come with maturing. Still, all this effort has not managed to completely dispel the irrational fear of a very rational process. One example is the Aging TikTok filter that has recently overtaken the platform—some people cry, some are purely shocked, and some are just plain lucky because there isn’t enough visible change to elicit a reaction. This is just to show that, really, there is one thing we struggle to give up when growing up—our sense of self associated with our looks. The anxiety surrounding aging runs deep, and honestly, looking at the art-historical evidence of how women and aging have been represented, it is no wonder. In what follows, I would like to suggest that while we all understand that growing old is a part of life, there is a good reason (albeit culturally fabricated) for feeling unsettled by it, visually. Let us look at some images.

I want to start with the trope of the witch. Since Early Modern times, artists have explored it through the visual attributes associated with the bodies of elderly women. Interestingly, witchcraft during the Renaissance was linked to the idea of lust. Take a look at German artist Albrecht Durer’s print The Witch, ca 1500. An elderly woman, depicted naked, rides a flying male goat, backwards. She is grotesquely represented, her nose crooked and her breasts sagging. According to The Witches’ Hammer, the most famous treatise about demonology at the time (written by a German Catholic clergyman) the practice of witchcraft was heavily connected to carnal lust. This is symbolised in Durer’s print through several attributes—the free-flowing hair of the hag alluded to loose hair’s ability to draw attention and distract men from worship. At the same time, the male goat was a sexual symbol associated with the devil. Further associations tie the witches to Eve and man’s original sin. A woman’s desirability and ability to express desire were hence disarmed by the grotesque rendition of the aged body.

Another example that distorts the female body to convey the form of the hag is the image of the Slavic witch Baba Yaga. She is a consistent character in Slavonic fairy tales who usually eats children or puts them through some challenge. She is hence a type of expression of collective consciousness through folklore—Baba Yaga is a liminal character, uniting concepts of motherhood, fertility, regeneration, and death. Russian illustrator Ivan Bilibin’s depicts her in the woods, riding her mortar and pestle and swiping her traces with the broom. Baba Yaga’s features are distorted, her nose huge and bluish, her face androgynous. Her hairy arm ends with a hand, which holds the broom and is disproportionately large and brown, bearing connotations of necrosis. The mortar and pestle here assume a visibly phallic character. The cultural preconception that the woman as a hag marks a deviant body, suggests that ‘disorderly’ women undermine as well as reinforce social order.1 I personally subscribe to the idea that as a grotesque woman, Baba Yaga occupies a liminal space between chaos and order. Her ugliness also recalls the fact that in patriarchal society the biggest sin a woman can commit is to be ugly. This dispenses of the woman’s role as a sexual object regardless of what other qualities she may possess. It brings forth the idea that the ugly has a dangerous and potentially aggressive core as it foregrounds the monstrous, the impure, and the repugnant.2 All of this stems from the archetype of the crone: when a woman goes past child-bearing age and enters old age, she becomes socially dispensable because of her potential to dislocate masculine authority. This is because it allegedly takes a lifetime to acquire the secret knowledge associated with sorcery. Sadly, it is also because the changes that women’s bodies undergo after menopause were seen as making their bodies less feminine and more masculine.3 To put it bluntly, aging=ugliness=power=danger. The visual ridicule, however, is capable of obscuring the subversive potency of these images, if we do not read them carefully.

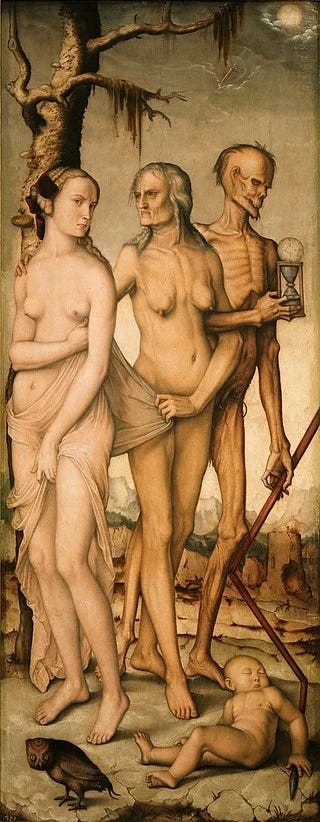

Yet another way in which the elderly female body has been employed is as a memento mori—a reminder that death is inevitable and our time here is limited. Old women and time have been bedfellows since ancient times—think of the Fates in Greek mythology who ensured everyone lived out their destiny as assigned by the universe. On the other hand, a not-so-flattering rendition of old age is seen in Flemish artist Hans Baldung Grien’s painting The Ages of Woman and Death, 1541-44. Here we observe a skeletal personification of Death holding an hourglass and pulling a nude old woman. The old woman is turning away from Death and toward a younger version of what seems to be herself. On the ground, there lies a baby. This is a brutally detailed vision of the female body as it matures and grows old—we even get a glimpse of what it looks like in the grave.

Another such wonderfully horrid example would be Fransico de Goya’s painting Time and Old Women, 1810. This is actually a satire of the Spanish Queen at the time, renowned for her vanity and ugliness. We see the allegorical winged figure of Time looming behind the grotesque figure of the Queen, while another brutally distorted old woman holds up a mirror in front of her. On the back of the mirror we read ‘Que Tal?’ which means ‘How is it going?’ Apparently, not great—time stops for no one, regardless of which social class they belong to. Despite the moralistic overtones, one thing is clear—old women were an easy target for ridicule.

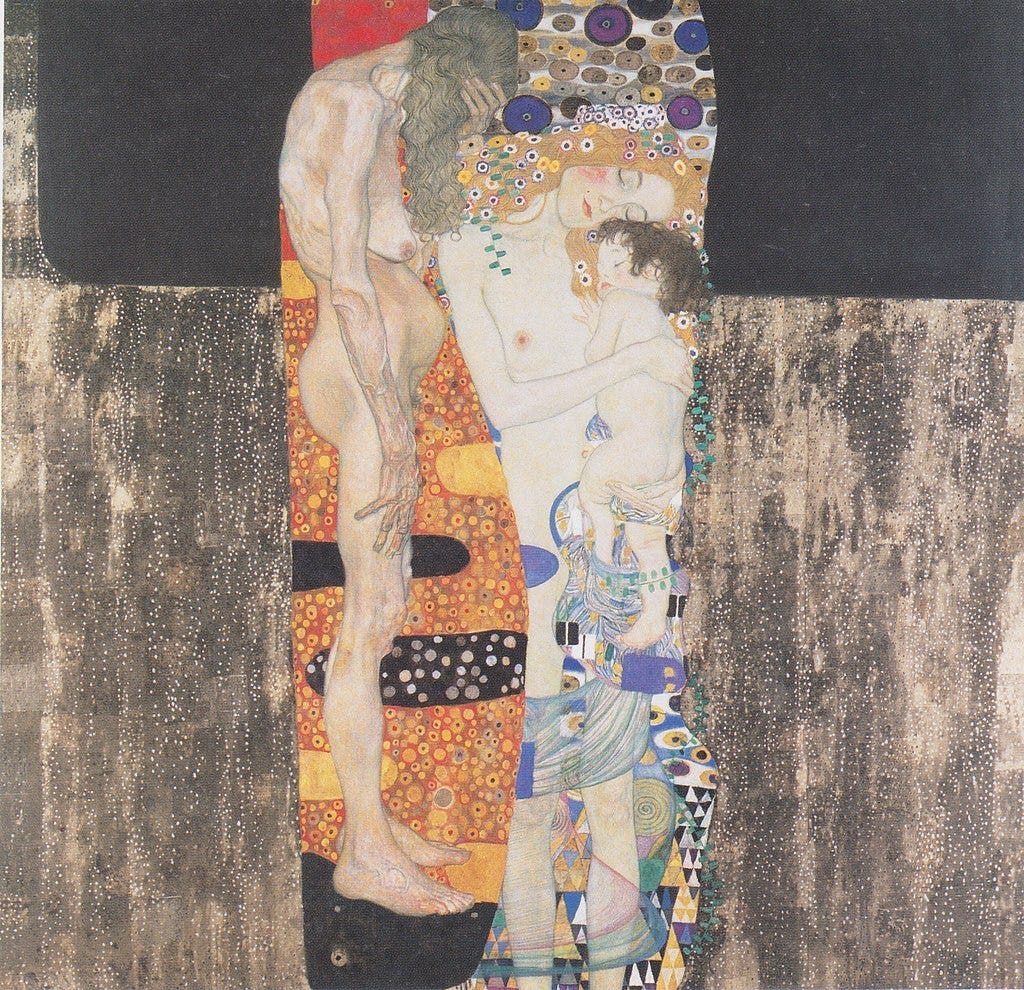

By the early twentieth century, ridicule was replaced by what was doubtless considered artistic honesty. Gustav Klimt’s painting The Three Ages of Woman, 1905 is a prime example of Viennese Secessionist painting. Three women are the focal point of the work—a beautiful red-headed nude holds a sleeping child, while an elderly woman stands next to them, full-length and in profile. It is a merciless depiction of old age. Her back is curved, shoulders drooping, breasts sagging, and belly rounded. Her gray hair and her hand cover her face—this denotes pure sorrow.

Now, you may have noticed that all of these images were created by men. It is interesting that the parts of the female body that male artists have consistently chosen to emphasise as the visible apex of the aging process are a woman’s face and breasts—two very vulnerable body parts, often associated with femininity and often scrutinised by women themselves. How have women artists seen themselves? There are very few pre-twentieth-century examples, but a particular favourite of mine is the Renaissance artist Sofonisba Anguissola’s Self-Portrait in Old Age, 1610. She was a highly accomplished painter in her lifetime and a student of Michelangelo. This painting is one of many self-portraits she produced and it depicts her seated, holding a book and a piece of paper. Dressed in black, she portrays herself in reserved and modest attire, as a respectable and educated woman. To me, this is a painting of great honesty and peace with the changes brought on by aging. The contrast with Klimt’s sorrowful old woman could not be sharper.

I would like to end by looking at Alice Neel’s Self-Portrait, 1980. Neel was an artist who spent a major part of her career painting portraits of other people and eventually became renowned for her intense, expressionistic approach to depicting her subjects, as she saw them, often in the nude. It took her a while to finally paint herself, aged 80. She depicted herself sitting in an armchair, holding a paintbrush and handkerchief, and fully naked with the exception of her glasses. This is doubtless one of my most beloved self-portraits because it takes a certain level of vulnerability, but also because there is nothing ugly or grotesque about it. Rather, it commands respect—Neel looks out at the viewer, showing the tool of her trade, suggesting that this is the body of a woman who has spent a lifetime painting other people’s bodies. Sh

e confronts old age head-on, and there is something very comforting about it.

In the end, it is hard to come to terms with the inevitability of physical change. But what we can do is recognise that the anxiety surrounding it has been perpetuated by the pervasiveness of the association of old age with ugliness. What we could do to dispel this idea is a tricky question. Perhaps looking at art could be one way to start.

Erica McWilliam. “THE GROTESQUE BODY AS A FEMINIST AESTHETIC?” Counterpoints 168, 2003, 219

McWilliam, 2003, 220

Hofrichter, Frima Fox and Yashimoto, Midori, Women, Aging, and Art: A Crosscultural Anthology, Bloomsbury Academic, 2021, 2

Fascinating study! Thank you :)

I actually kind of like it. I'm grateful to still be alive after cancer, and equally grateful I don't have to be performatively "attractive" in the young person sense anymore. It was a burdensome and artificial imposition of a sick society.